Nadia Jelassi and Mohamed Ben Slama, whose works were shown at an exhibition in La Marsa in June 2012, could face up to five years in prison if found guilty. Their multimedia work had provoked demonstrations during the exhibition.

“Prosecutors have repeatedly used criminal legislation to stifle critical or artistic expression,” said Eric Goldstein, deputy director of the Middle East and North Africa division at Human Rights Watch. “Bloggers, journalists and now artists are being prosecuted for exercising their right to express themselves freely”.

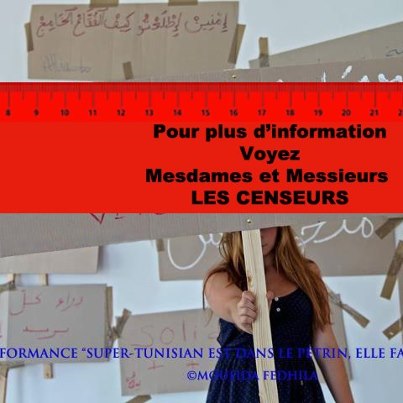

Jelassi’s contribution to the exhibition “Spring of the Arts” was a work entitled The One Who Has Not …, containing sculptures of veiled women emerging from a heap of stones. Ben Slama’s contribution represented a line of ants emerging from a schoolbag and forming the word “Subhan Allah”.

The investigating judge of the Tunis Court of First Instance informed the two artists in August that they were being prosecuted under Article 121.3 of the Criminal Code.

The exhibition was held from June 1 to 10 in a palace belonging to the state known as Al Abdelliya in La Marsa, on the northern outskirts of Tunis. On 10 June, around 6 pm, three people, including a bailiff, asked one of the gallery’s directors to remove two paintings they deemed insulting to Islam. Meanwhile, a campaign was growing on Facebook, condemning the show as anti-Islamic. That night, dozens of people broke into the palace and vandalized some works of art before the police dispersed them. On June 11, riots broke out in several parts of the country, with protestors setting fire to tribunals, police stations and other public institutions. A civilian died in the violence and dozens were wounded. Several preachers, in mosques throughout the country, condemned the art exhibition, some openly calling their faithful to put the artists to death as apostates.

Jelassi told Human Rights Watch that she had received a phone call from the judicial police a few days after the incidents, informing her that an investigation had been opened into the “Al Abdelliya” events. On 17 August she went to the Tunis Court of First Instance, at their request, and the investigating judge of the second office informed her that she was accused of “harming public order and good According to Article 121.3 of the Criminal Code. On 28 August, the investigating judge questioned her.

“I felt like I was in the Inquisition,” she told Human Rights Watch. “The investigating judge asked me what were the intentions behind my works visible at the show, and whether I wanted to provoke people through this work.”

The United Nations Human Rights Committee has proclaimed that laws prohibiting speeches that are deemed disrespectful of a religion or other belief system are incompatible with international law, apart from the very limited circumstances in which religious hatred is tantamount to inciting Violence or discrimination.

The case is at least the fourth in which prosecutors have used Article 121.3 of the Criminal Code to issue charges for speeches deemed contrary to good morals and public order since the constitution of the new National Assembly Constituent body of the country in November 2011. On 28 March, the Mahdia Court of First Instance sentenced two Internet users to seven-and-a-half-year prison sentences for publishing writings perceived as insulting to Islam.

On 3 May, Nabil Karoui, the owner of the television station Nessma TV, was fined 2,400 dinars (US $ 1,490) for broadcasting the animated film Persepolis, denounced as blasphemous by some Islamists. On March 8, Nasreddine Ben Saida, publisher of the newspaper Attounssia, was fined 1,000 dinars for publishing a picture of a football star embracing his naked girlfriend.

Article 121.3 of the Criminal Code defines as an offense “distribution, offering for sale, exposure to the public and possession for distribution, sale, exhibition for propaganda purposes, Of leaflets, bulletins and butterflies of foreign or foreign origin, such as to harm public order or morality “.

“Many Tunisians expected that repressive laws such as Article 121.3 would not survive long after the dictator who had them adopted,” concluded Goldstein. “We now observe that as long as the provisional government does not set itself the priority of getting rid of such laws, the temptation is irresistible to use them to silence those who disagree or think differently.”

To read more Human Rights Watch releases on Tunisia, please follow the link http://www.hrw.org/fr/middle-eastn-africa/tunisia

Press

{mainvote}

َAbonnez-vous

َAbonnez-vous